Have you ever seen the iconic gateway that seems to be floating on water? That’s the famous Torii of Itsukushima island (or Miyajima), in the southwestern part of Japan. A Torii is an archway to access a Shinto shrine. It's well known that in Japan, people often practice Shinto as well as Buddhism or another religion. In fact, there are around 100,000 public Shinto shrines in Japan and over 75,000 Buddhist temples.

But can we consider Shinto to be Japan’s main religion? When was it introduced to Japan? And what are Shinto practices?

Keep reading to find out these answers and much more about Shinto festivals.

What is Shinto?

Shinto originated in Japan, and it is often regarded as Japan’s indigenous religion. It involves the worship of several gods called kami, 神. They are supernatural entities, formless and invisible, believed to inhabit all things. They can be mountains, rivers, or natural forces, including disasters like earthquakes or plagues. This is why it's considered a natural religion.

But is it a “religion” as we intend it?

In fact, there is no central authority in control of Shinto or a sacred text. Also, significant diversity among practitioners exists. There are no compulsory religious services (as compared to Christian weekly services). People can visit shrines at their convenience. But there are beliefs, practices, and sacred places that are common to all.

What are Shinto’s basic beliefs?

One of the most important things about ancient Shinto is believing in the idea that divine and human nature are essentially one thing. This is also the base of today’s Japanese culture: everything is connected.

Gods give life to human beings. After death, their souls, purified by rituals, can become kami too. They will become the ancestors who protect their families and their happiness.

Praying for the ancestors' souls is also an important religious concept. In fact, in Japanese houses, everyone has a Kamidana, 神棚, a miniature household altar. They are generally located on a shelf in a bright space. Here, the family can offer rice, sake, water, and salt and pray to the kami and the ancestors' souls.

This idea of connection between living things still resonates deeply with Japanese people. This is what makes them so respectful towards nature and other humans and helpful to one another.

Who are Shinto gods?

Shinto Gods are called kami, 神. Japanese people usually refer to them with the word kamisama, 神様, which is more respectful. It is often said that eight million kami exist, and Shinto practitioners believe that they are present everywhere.

According to traditional texts, there are different kinds of Kami. They can be amatsukami or kunitsukami. The first ones are anthropomorphic protagonists of mythological stories and legends. The second ones are the Gods of nature and the earth, who inhabit natural things such as the Sun, a mountain, or a river.

Amatsukami 天津神

Izanagi (He Who Bechoked) and Izanami (She Who Beckoned) are the ones who created Japan itself and the human race. Their story can be read in the famous chronicle of myths, the Kojiki (古事記), one of the two ancient texts from the eighth century.

Amaterasu Ōmikami, 天照大神, is the goddess of the Sun. She is one of the major deities of Shinto, the daughter of Izanagi and Izanami. She is depicted in the Kojiki as the mythical ancestress of the Japanese imperial house.

His younger brother, Susanowo, スサノヲ, is the “Raging man”, god of seas and storms.

Kunitsukami 国津神

Kunitsukami are more humble and have Nature-related names. The Goddess of mountains and woods, 山の神 yama no kami, can inhabit any mountain.

Depicted as a wise man holding a rice bowl and a spoon, the god of rice fields, 田の神, ta no kami, will bring prosperity to a new couple. In the marriage ritual in Kyūshū’s villages, his smiling statue is put in front of the couple to wish them prosperity.

Inari (稲荷) is the god of rice. As rice is the basis of Japanese nutrition, Inari became a powerful and elusive God. In ancient times, rice was even used as currency, so she was also the patron of merchants. His messengers are the white foxes, kitsune - 狐, who can give or remove wealth and take control over humans.

The two kitsune are guarding the Inari shrine at Fushimi Inari, in Kyoto.

When did Shinto start in Japan? - The Origins of Shinto

Shinto religion doesn’t have a “founder” like others. There wasn’t even a name for this faith, not until a foreign one came. In Japan, people have venerated kami since prehistory. It is not possible to track its origin, but it's very ancient, probably existing since the Neolithic age.

The introduction of a foreign religion: Buddhism

Around the middle of the 7th century, Buddhism began to spread in the Japanese islands. It was the ideological expression of the advanced Chinese society. For this new doctrine, the word Bukkyō, 仏教 was used, meaning “Buddha’s teaching”.

To distinguish it from the indigenous belief, the word Shintō was coined, written 神道, which means literally “the way of gods."

From this point on, Buddhism influenced Shinto deeply. To understand this process, we must consider that in the nearest countries, like India, China, and Korea, Buddhism became the predominant doctrine, and existing ones were suppressed or diminished. For example, Taoist deities came to be worshipped as the guardian deities of Buddhist temples.

How can Shinto coexist with Buddhism and other religions in Japan?

In Japan, however, the first step was to find a new interpretation of the Shinto deities from the point of view of Buddhist doctrine. Japanese kami were neither rejected nor “downgraded.” But they did transition from their traditional, formless nature to being depicted anthropomorphically. New religious schools that blended Buddhism with the indigenous Japanese beliefs were formed, and new, separate temples for Buddhist practices were built. Eventually, some of them integrated the existing Shinto deities. This “fusion” between Shinto ideologies and Buddhist beliefs continued for centuries.

When European missionaries arrived in the 1500s, they received the same treatment as the Buddhists. Soon, their practices and rituals were also integrated into the customs of the Japanese people.

Sakoku, the Japanese isolationist policy

This policy of cultural and religious integration continued until the Tokugawa Era (from 1600 to 1868). This Era is well known for the isolationist policy called Sakoku, 鎖国, “national isolation.” The Japanese government limited all foreign trade and contact for more than 200 years. At the beginning of the Meiji period (1868 to 1912), it focused on creating a national “cultural identity,” finding its roots in the traditional Shinto beliefs. This influenced the religious sphere as well, and so Kokka Shinto, 国家神道, “the national Shinto”, was enhanced. This happened when the nationalist ideology spread in Japan at the beginning of the 20th century. But Buddhism, together with the Taoist and Confucian beliefs, were not abandoned.

Nowadays, it has become common for a Japanese person to practice a purifying Shinto rite at birth, receive education about Taoism concepts (like yin and yang), marry with a Christian or Shinto ceremony (or even both), and then have a Buddhist and a Shinto funeral rite.

It's proof that Japanese people believe that various religions and beliefs can coexist harmoniously.

How do Japanese people practice Shinto?

Shinto consists of participating in festivals, rituals, and praying kami. You can pray or kami privately at home or at a shrine.

Praying for the kami is not easy: each of the gods has an inner strength that can be destructive or peaceful. It’s up to men to control and calm this strength through rituals. The effectiveness of a Shinto ritual depends on the perfection with which it is executed. This requires a large amount of concentration, which will purify the soul of the performer and make him able to communicate with the god. The person in charge of the shrine’s rituals and its maintenance is the kannushi, 神主, the shinto priest. One or more miko, 巫女, a maiden in service of a Shinto shrine, can assist him.

A kannushi and a miko taking the newlyweds (and the bride's mother) to the inner shrine for the marriage ceremony

Many Shinto rituals started in ancient times, most of them connected to the annual rice cultivation phases. Today, national festivals are timed to coincide with the most important ones. For example, Oshougatsu, the New Year, and Obon, at the end of summertime, are two important festivities. You can get some rest from work all over the country, as they are National holidays. These days correspond to the period when there was the least work to do in rice camps (and so, more time to have fun!). On New Year’s, fields can rest under the snow. In August, wheat spikes are already grown, and there’s no need to work in the camps anymore.

Curiosities: New Year’s religious tradition

We can think of some New Year’s practices to understand how deeply Shinto and Buddhism coexist in Japan.

The Buddhist "New Year's bell"

A Buddhist tradition that remains today is the Jōya no kane, 除夜の鐘, the “New Year’s bell.” Around midnight on New Year’s Eve, the bell of the nearest Buddhist temple will begin to ring and strike 108 times. This is the number of the mundane temptations humans must resist to find Nirvana.

The Shinto mochi and hatsumoude

The Kagami mochi too, 鏡餅, the “mirror rice cake”, is related to a Shinto tradition. In ancient Japan, Mirrors had a round shape. They were often used for Shinto rituals because they were believed to be a place where gods lived. And so the Kagami mochi is round-shaped, recalling the mirror's shape, to celebrate the new year together with kami.

Furthermore, on the first days of January, it’s important to join in the hatsumoude, 初詣. It’s New Year’s first visit to the shrine, where family and relatives pray together for a fortunate year ahead. A difference between this visit and a normal one is that you can ring the bell near it after throwing some coins into a box in front of the altar.

Shinto shrine or Buddhist temple? How to recognize them

Shinto shrines are called Jinja, 神社, with the kanji for “god” plus the one for “sanctuary.” In Japan, you will easily recognize them by the presence of a Torii, 鳥居, the gateway to access a Shinto shrine. These iconic archways have become symbols of Japan. Think about the famous Itsukushima Torii on Miyajima island, which appears to be floating on water. However, there are no Torii before a Buddhist temple, so this is the easiest way to recognize them. You can find Torii made of bare wood or stone, but they are more commonly painted in red. Besides the practical function of preserving the structure, the red color is said to ward off evil spirits, danger, and bad luck.

To learn more about how to visit a Shinto shrine, follow our guidelines here!

How’s a religious festival for the Japanese?

A matsuri, 祭り, is a festival sponsored by a local shrine or temple and organized by the local community. People participating in it will wear a typical matsuri costume, or something recalling an ancient era. They will carry a heavy mikoshi (神輿) around the streets, a sacred portable shrine. The purpose is to bless the town and the people living in the community.

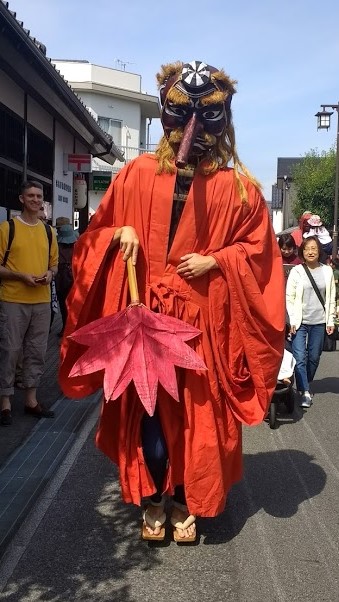

Following the parade through the streets, you can also find a Tengu, 天狗, a monster with a human body, red face, long nose, and wings. It's regarded as a mischievous being, but sometimes as a helpful mountain guardian.

During the parade, beware of participants embodying a Tengu!

Dancing and snow matsuri

There can be a dancing performance or an artistic competition along the way, like in the Awa Odori matsuri. Here in Tokushima, Shikoku Island, men, women, and children dance on the streets of the city. This happens from the 12th to the 15th of August, as a part of the Obon. They wear the traditional summer kimono, the yukata, 浴衣, and straw hats. More than a million people get together each year for this festival, so it's said to be the largest traditional festival dance in Japan,

In Hokkaido, the northern island of Japan, yuki (snow) matsuri takes place in Sapporo city in February. It started in 1950 when a high school student built six snow statues in Odori Park. Since then, it has become an international contest of spectacular snow and ice sculptures, attracting more than two million visitors from Japan and across the world.

Dashi and hadaka matsuri

Once every 5 years, in Handa City, the Handa dashi matsuri, 半田山車祭り, takes place. 31 dashi (floats) go on parade all together. These dashi are 8 meters tall and decorated in full measure. It's a tradition that goes back to the Edo period (1603-1868). About 30 or 40 colorfully dressed men will carry the dashi. You will hear them cheering on each other by shouting “Wasshoi!” which is an Edo-period word meaning “to stay with harmony.”

Furthermore, the Japanese practice different hadaka matsuri, 裸祭り, the “naked festivals”. Here, participants can wear nothing or a minimum amount of clothing. It’s the fundoshi, 褌, a traditional men’s underwear made of a long piece of cotton cloth. The meaning of naked matsuri is to exhibit virility by participating in strength contests. The real purpose is to win the competition by collaborating with each other.

One of the 31 dashi at the Handa dashi matsuri, with participants carrying it along the streets

Hope you enjoyed discovering Shinto practices!

Author: Valeria (graduated from Ca’Foscari University Japanese Studies)